March 6, 2015

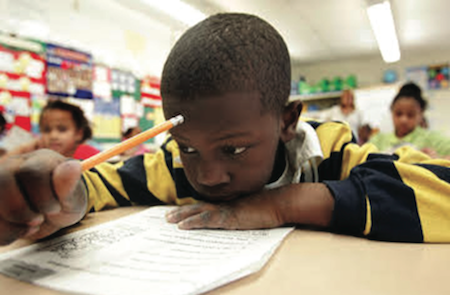

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NNPA) — According to a report released last week, 3.5 million K-12 public school students were suspended in the 2011-2012 school year – enough to fill every stadium seat in Super Bowl I through Super Bowl XLV.

And Black children are bearing the brunt of these excessive suspensions.

The report, “Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?,” states, “Demographically, the seven highest-suspending districts all had majority Black enrollment, although the range was from 26 percent to 99 percent Black. Only one [of the seven highest], Taylor, Florida, was majority White, at 67 percent.”

The research, conducted by the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, offers a detailed analysis of public school suspension over the last few years, with the data broken down by elementary and high school, district and state, race and gender, and language and learning ability.

In the past two to five years, schools have made a concerted effort to avoid out-of-school suspensions for elementary schoolchildren, though it still happens. The reversal is not happening as fast at the high school level.

Black high school boys are suspended at the highest rate of all groups – 28.4 percent, compared to the 10 percent national average. Black high school girls follow at 17.9 percent (Native American and Latino boys come next, with 15 and 14 percent, respectively). Between 2002 and 2006, the suspension rate for Black girls increased at the highest rate of all groups.

For Black students with disabilities, the rates are even higher – 33.8 percent for Black high school boys, and 22.5 percent for girls – “shocking” enough to suggest that these students’ civil rights are being “unlawfully violated.”

Out-of-school suspensions also feed the racial and economic achievement gap, and have far-reaching effects on future outcomes.

“…higher suspension rates are closely correlated with higher dropout and delinquency rates, and they have tremendous economic costs for the suspended students, as well as for society as a whole,” the report explains.

“Therefore, the large racial/ ethnic disparities in suspensions that we document in this report likely will have an adverse and disparate impact on the academic achievement and life outcomes of millions of historically disadvantaged children.”

The starkness of the data has lead schools, administrators, teachers, and parents to believe that Black children must be earning these suspension rates. But an examination of the data at the state and district level shows does not support this belief.

For starters, Black students are enrolled in almost equal numbers in both high-suspending and lower-suspending states. Since 2009, suspensions in the 35 school districts with the lowest suspension rates have continued to decline.

“In other words, readers would be wrong to assume that something about the behavior of Black elementary students requires greater use of suspension,” the report says. “To the contrary, these data, along with several studies that tracked behavior ratings of students as well as disciplinary outcomes suggest that Black students are punished more harshly and more often for subjective minor offenses. Instead, researchers conclude that school policies and practices more than differences in behaviors, predict higher suspension rates.”

In addition to a race and gender analysis of the suspension data, the researchers examined and ranked the data, district-by-district and state-by-state. Florida suspends its students more than any other state, both at the elementary and high school levels. Other K-12 high suspending states with high suspension rates in both elementary and high schools were Mississippi, Delaware, Alabama, and South Carolina.

Notably, Missouri is home to three of the highest-suspending school districts in the nation and has the highest Black-White discipline gap. Michael Brown, the unarmed Black teenager killed by a White policeman in Ferguson, Mo., was a graduate of Missouri’s Normandy School District, where students are suspended at a 48.4 percent rate.

The worst districts for Black students in particular are Oklahoma City in Oklahoma, Cahokia CUSD 187 in Illinois, and Greenville Public Schools in Mississippi – where Black kids are suspended at 64, 63, and 59 percent, respectively. In Oklahoma City, that number is 75 percent for Black boys; in Cahokia, it’s 58 percent for Black girls.

There were also districts that have done well in reducing out-of-school punishments, especially among Black children, including: Edgewood ISD in Texas, Richmond County in Georgia, and Lawton County, Oklahoma.

States with large Black populations that have improved over the last few years include Maryland, Pennsylvania, and California.

While excessive school suspension remains a significant barrier to equitable, effective public education for all children – so much so that the Justice Department issued civil rights-based discipline guidelines to schools last year – strides are being made.

The report states, “Although we anticipate that newer data will reveal substantial improvements in some states and districts, there is no question that much more reform is needed if we are to be successful in closing the school discipline gap.”

Jazelle Hunt, a Washington correspondent for the National Newspaper Publishers Association News Service, recently completed week-long training at the University of Southern California as one of 14 journalists awarded a 2014 National Health Fellowship. Hunt is a Howard University graduate.