May 8, 2015

Photo courtesy of NNPA

A growing number of medical experts say the damage inflicted extends far beyond the number of actual victims.

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NNPA) – Police have killed at least 369 people in the first four months of 2015, with 103 Black Americans – 28 percent – making up a disproportionate number of the victims, according to Ferguson protester project, Mapping the Police.

But a growing number of medical experts say the damage inflicted extends far beyond the number of actual victims.

Unarmed Black male victims are currently en vogue in the media, with images of the victims’ last moments on loop hour after hour. And each incident adds a fresh layer of offense – from Deputy Robert Bates in Tulsa, Okla., who was charged with the manslaughter of Eric Harris but allowed to vacation in the Bahamas after the court hearing, to Officer Dante Servin in Chicago, found not guilty for Rekia Boyd’s murder because the prosecutor deliberately filed lesser, inappropriate charges.

“The repetitive nature of this, the fact that this is chronic…. Chronic experiences of racial discrimination, and I’d include vicarious discrimination, can influence mental and physical health outcomes,” says Amani Nuru-Jeter, associate professor of public health at University of California-Berkeley and researcher on racial health disparities. “I’m not saying it’s the same as post-traumatic stress disorder, but we do see some similarities in how people cognitively respond.”

Other depressive or schizophrenic symptoms (such as paranoia or emotional numbness) can emerge, as well as physical health problems such as cardiovascular disease. On an individual level, racism in general has gradual, but potentially life-shortening effects on the mind and body.

These effects can be even more acute for those who make their Blackness the most important part of their self-identity, and/or those who internalize the racism against them.

“We found that it’s associated with ‘cellular aging,’” Nuru-Jeter says, referring to a body of public health research to which she has contributed. “We used a measure called telomeres, which are biological indicators of the age of the cells in our bodies and indicate premature biological aging.”

On a communal level, being under the threat of police violence backed by the authority of the local, state, and sometimes national government, is enough of a burden on its own. When this oppression stretches from the mundane to the life threatening – such as the discriminatory fines up and the National Guard deployment in Ferguson after Officer Darren Wilson was not indicted – it is easy for Black communities to fall into a sense of hopelessness.

The more a community feels bound by the same identity (be it racial, socioeconomic, or otherwise), the more deeply the effects of chronic racial discrimination are felt.

“There’s also collective racial identity. There’s [an academic field] called social capital…and in that, there’s a concept called bonded social capital,” Nuru-Jeter explains. “Identity can increase solidarity. For example, what we saw in Ferguson was an outcry of, ‘We’re tired of being treated like this, we’re raising our voice to say Black lives do matter to us.’”

There’s also the matter of images. Some media outlets have routinely reported on the victim’s past crimes and encounters with the justice system, and used either an old mugshot or image of the victim dead or dying to accompany their coverage.

Some outlets have come under fire for what many consider insensitive treatment of the deceased. One Change.org petition specifically asked The Washington Post to stop using victim mugshots in covering police violence. After some outcry on social media, CNN began to air a blurred version of the footage of Walter Scott’s killing, as captured by bystander, Feidin Santana.

Nuru-Jeter points to neuroscience research involving FMRI scans (which map both brain activity and structure) that show how images or films can create a vicarious experience for the viewers.

“Some of these studies show that the same parts of the brain light up compared to when people have their own experience. I’m extrapolating here, but the suggestion is [there],” she says, especially for people who see themselves and their loved ones represented in the victims on TV.

As police killings continue to be a hot topic in the news – and as police departments continue to use lethal force in their interactions with civilians – it is likely that media coverage of this violence will continue. Nuru-Jeter highlights two ways to protect one’s self and loved ones from the mental toll of these tragedies.

First, having strong racial identity can be a buffer, if it is experienced in a proud way. By focusing on Black pride, and drawing strength from the positive aspects of the Black American experience, individuals and communities can balance out the painful parts.

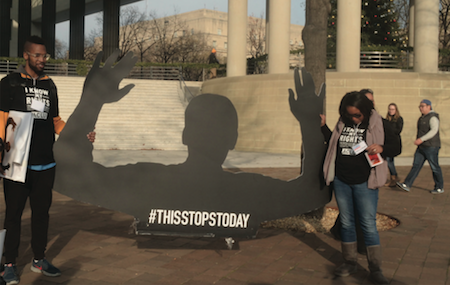

Finally, supportive people and systems are key for overall wellbeing. “What happens when we see a constant message of devalued Black life in society? One way people can cope with this is to share the experience, and not hold it in,” she says. “Even if you’re not getting individual support, simply being a member of a group [as in protest] can help. ‘There’s strength in numbers’ counts as a cliché, but I think the evidence is there to support that.”

Jazelle Hunt is a Washington correspondent for the National Newspaper Publishers Association News Service.