May 8, 2015

Pamela Newkirk, journalist and author of the book said that, “For more than a hundred years, the story of Ota Benga was told by the same people who exploited him, and that narrative has stuck all of this time.” (Courtesy Photo)

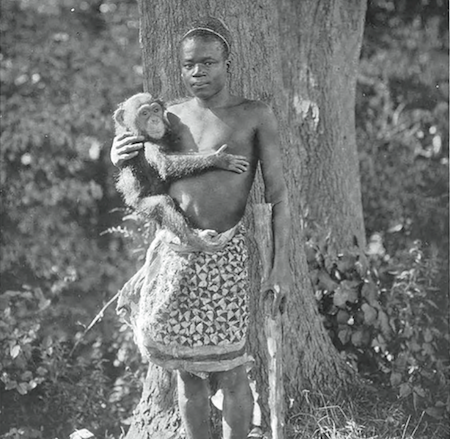

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NNPA) – An ordinary Internet search on Ota Benga yields black-and-white photos of a petite Black man, almost naked, smiling with a row of spiky teeth. Some accounts say he achieved fame in the early 1900s as part of controversial human zoo exhibitions in the United States.

But a look below the surface reveals a true tale of extreme racism, cruelty and widespread collusion in the kidnapping and dehumanization of a man.

This is the meat of Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga, a shocking historical biography of Benga’s experience as a museum attraction – most notably as “the pygmy at the [Bronx] Zoo,” on display in an enclosure with an orangutan in 1906. Benga was later relocated to Lynchburg, Va, where he committed suicide.

African Pygmy, Ota Benga and Chimpanzee. From a photograph made in 1906 in the Zoological Park, New York City, 1979.

Due on book stands in June, the historical biography retraces Benga’s journey using primary sources such as published articles, museum archives, and first-person writings from Samuel Phillips Verner, the man who abducted Benga and brought him across the Atlantic.

“So much of what I read in the archives was so chilling,” says Pamela Newkirk, journalist and author of the book. “And I guess the thing that surprised me was the extent to which the statements of elite men and institutions go unquestioned. For more than a hundred years, the story of Ota Benga was told by the same people who exploited him and that narrative has stuck all of this time.”

Currently, Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo, published in 1993, is the book of record for learning more about Benga’s life and death. It tells the story of Verner’s exploits as a missionary in the Congo, his fascination with the racist scientific theories of the day and his guilt over his treatment of Benga, all culminating in a tenuous friendship between Benga and Verner. This book’s co-author is Verner’s grandson, who died in 2013.

As Newkirk gathered primary sources, she was surprised to find so many news articles, scholarly studies and first-person accounts, written in real-time as Benga’s life unfolded. And despite clear evidence, some academics were reluctant to have the narrative disturbed.

“There were some institutions that were not as forthcoming as one would hope,” she says.

“ButI did find a lot more than I ever thought I would. Even if one institution had withheld information, there was a lot more, so I wasn’t overly reliant on one place.”

In reading, she began to understand why some sources seemed so guarded. “One of the main things I found is that he was hunted, like one would hunt an animal,” Newkirk says, referencing an article Verner had written about his method for capturing the people derogatorily called pygmies. “He was in no way complicit in his exhibition and he resisted being there. Stories have been told as if he was a happy subject of that degradation.”

According to Newkirk’s research, scientists and anthropology pioneers were among the first and loudest to defend and justify Benga’s confinement. Newkirk explains that the theme of the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in 1904 – also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, the first place Benga was held captive – was human advancement. Many indigenous people from around the world were kidnapped or coerced into performing in exhibits depicting man’s progress from “savage” settlements to the “civilized” White Western world.

“It was all predicated on notions of science and anthropology. When The New York Times defended the [Bronx Zoo] exhibition, they defended it in the name of science,” she explains.

“There were questions of whether or not he was human, whether he was The Missing Link. It was the most eminent men of New York City who defended and supported this exhibition.”

Newkirk, who is also the director of undergraduate studies at New York University, where she teaches about media representation of marginalized groups, draws parallels between the racist beliefs that enabled what happened to Benga and today’s racial climate.

She says, “The refrain of ‘Black Lives Matter’ rings in your ear when you see what people are capable of doing. They said that the African is so close to the ape…. When you look at what was considered ‘educated’ and ‘modern’ and ‘advanced,’ those were the views that were considered progressive in that period.

“This is so deeply rooted in American society – this idea that Black people…are animals. My book is historical…but I leave it to others to see how deeply embedded these ideas are and how they became…the foundation for policy.”

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga goes on sale June 2. Pre-orders are available now through Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Newkirk hopes that her book is instrumental in correcting the historical record of Benga’s life in the United States.

“The most important thing for me is to correct the historical record. It’s just such an insult that the man who’s most responsible for exploiting him has been depicted as his friend and savior for a hundred years,” she says.

“[Benga’s] life was worthy of this kind of exploration, because Black lives do matter. I think we owe that to Ota Benga.”

Jazelle Hunt is a Washington correspondent for the National Newspaper Publishers Association News Service.