March 27, 2015

Beginning as International Women’s Day in 1911 and eventually becoming Women’s History Week by 1982, the designation of March as Women’s History Month became nationally recognized in 1987. Since then, it has continued its legacy of bringing the focus on women’s immense contributions to culture and society from margin to center. The women who fought and insisted on its existence understood personally and politically the importance of having visibility, representation, and a knowledge and pride of one’s history. Activist Marian Wright Edelman famously declared, especially in regards to the future of children: “You can’t be what you can’t see.” So, as Women’s History Month comes to a close, we are excited to dedicate this page to celebrate and honor women’s rich and diverse history and influence and have chosen to highlight these four revolutionary women:

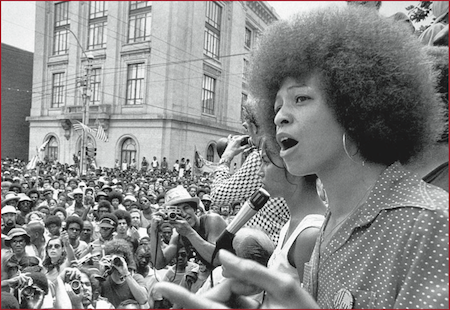

Angela Y. Davis

Perhaps one of the most respected and well-known revolutionaries, writers, activists, and intellectuals of the 20th century, Angela Davis has committed her life to the struggle for freedom and liberation of all oppressed people. Davis studied French and Philosophy, was a member of the Communist Party USA, and aligned herself with several social justice movements, including the Black Panther Party, Civil Rights Movement, and Feminist movement, among others. After being placed on the FBI’s most-wanted list in the early 1970s, Davis was acquitted by 1972 and continued to be an internationally known and respected activist. She worked as a professor Ethnic Studies, History of Consciousness, and Feminist studies as well as authored several pivotal books. She is a prison abolitionist who coined the now highly influential term “Prison-Industrial Complex,” and who cofounded Critical Resistance, a grassroots organization committed to dismantling the P-IC. Some of her works include Women, Culture, & Politics (1990), Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1998), Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003), and Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire (2005).

Ella Baker

Despite being one of, if not the most, influential woman in the Civil Rights Movement, Ella Baker’s incredible legacy and commitment to Civil Rights and Black Freedom is often obscured or simply written out of “mainstream” history. Baker emphasized a grassroots, collectivist, and egalitarian model of leadership, believing that a strong organization must be built from the bottom up. She despised elitism, and famously declared that “strong people don’t need strong leaders,” advocating for the power of the “little people” through a model and practice of participatory democracy. At the time of her activism, she was the highest-ranking woman in the NAACP, a highly respected member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and revered and referred to as the “Godmother of SNCC,” the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee. Her style of horizontal leadership and egalitarian approach to the struggle for freedom contributed greatly to the success of the Civil Rights Movement and was highly influential in subsequent social movements. Though her activism spanned five decades, Baker was notoriously private and left no written works behind. You can learn more about her through the 1981 documentary Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker and the biography Ella Baker & The Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003) by Barbara Ransby.

Gloria Anzaldua

Born in 1942 as a sixth generation Chicana on the U.S.-Mexican borderlands of Texas, Gloria Anzaldua used her experience as a poor, Indigenous-Mexican-white lesbian to inform her groundbreaking Borderlands Theory. As a writer and public intellectual in the ‘80s, Anzaldua challenged both the academy and society with her expansion of W.E.B. Dubois’ theory of Double Consciousness by arguing that people who exist within multiple, opposing, and oppressive social categories possess a unique consciousness of complexity, ambiguity, and creativity in navigating multiple and diverse social realities. Her inclusive and spiritual approach to social justice as well as contribution to Cultural, Feminist, Queer, and Intersectional theories were both innovative and radical, and remain relevant today. Her works include the seminal This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) and the foundational Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987).

Gerda Lerner

Credited with the creation of not only Women’s History Month, but also with teaching the first Women’s Studies course in the world, as well as establishing the nation’s first Ph.D. program in Women’s History at our own UW-Madison, Gerda Lerner’s influence on history and culture cannot be understated. Born in Vienna to Jewish parents in 1920, Lerner was forced to immigrate to the U.S. in 1939 during the Nazi occupation. With her husband, Carl, Lerner involved herself in multiple grassroots movements including civil rights, Communism, trade unionism, and early feminist and anti-racist organizations. Along with Civil Rights lawyer and activist Pauli Murray, Lerner cofounded the National Organization for Women in 1966. During this time and into the ‘90s, she steadily built the foundation for Women’s Studies to be taken seriously within the academy as a site of serious intellectual work. Lerner devoted herself not only to women’s history, but to African-American history as well. She authored Black Women in White America: A Documentary History (1972), a book that centered Black women’s history and experience within African-American history, a historical and racial narrative that had previously been overwhelmingly gendered as male. Lerner lived in Madison until her death in January 2013. Other important works include The Female Experience: An American Documentary (1976), Teaching Women’s History (1981), and Why History Matters (1997), and Fireweed: A Political Autobiography (2003), among many others.