April 3, 2015

“And he hugged me again, gave me a kiss and told me he loved me. That was the last time I saw him.”

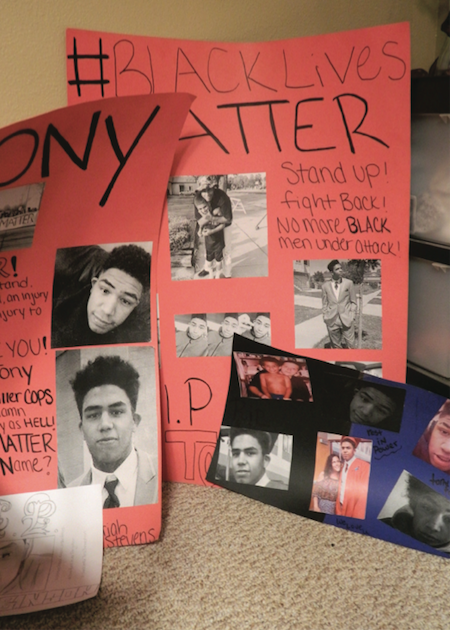

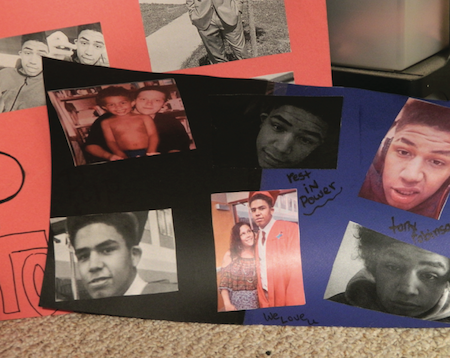

With friends, he went by Tony, but to family he was Terrell.

Standing well over six feet tall, he towered over his mother, whom he loved to pick on and pester, always trying to get a rise out of her. After annoying her for a bit, he would wrap his long arms around her, holding her tight until she finally gave into the hug.

“He was a typical teenager, always goofing around and playing,” remembered his mom, Andrea Irwin. “He was full of life.”

But that life ended a month ago in a way that was anything but typical.

In the early evening of March 6, Tony Terrell Robinson Jr. was shot and killed during an altercation with a Madison police officer. He was 19-years-old.

According to reports, Officer Matt Kenny was investigating a call about someone jumping in and out of traffic who was suspected of battering two others. After arriving at a Williamson Street apartment, Kenny and Robinson struggled and the officer was struck in the head and knocked down before drawing his weapon and shooting Robinson, who was unarmed. Kenny is white and Robinson is biracial.

As with all police-involved deaths, the incident is under investigation. The state’s Department of Justice’s Division of Criminal Investigation has concluded its part of that process and last Friday turned over its findings to Dane County District Attorney Ismael Ozanne, who will decide if Kenny’s use of deadly force was justified or if charges should be brought against the officer. It is unclear when the district attorney will make that determination.

The incident has drawn national media attention and led to multiple protests because of its similarities to other recent deaths of young, unarmed Black men at he hands of police elsewhere in the country.

A little over a week after his death, Robinson was laid to rest following visitation and funeral services that drew hundreds.

In the aftermath, a fair amount has been unearthed about Robinson. Those who knew him called him a ‘gentle giant’ who was a supportive friend and loving sibling. Others have painted him as a hoodlum, pointing to his conviction last year for an armed robbery that he was on probation for at the time of his death. There are also reports that he may have been on hallucinogenic mushrooms the night of the incident, which altered his mindstate and mood, though toxicology reports have not yet been released.

A Night Owl Since Birth

For Robinson’s mother, all that’s left are his few possessions and the memories. She sat down with The Madison Times last week to share some of those memories and thoughts about her son’s tragic death.

Her first son was the easiest of her three pregnancies despite being his birth being well past the due date.

“Terrell was 12 days late,” Irwin said of her son’s birth during an interview at her home on the city’s far south side. “He was a night owl, which stayed with him his whole life.”

He was the first grandchild and nephew in her family, “so he was spoiled,” she continued. “He was an easy going kid, always all smiles.”

The family moved around the Madison area a lot during Robinson’s childhood and lived in Tennessee for the two years before he started school.

Robinson played for the Warner Park Youth Football program as a lineman, using his size to his advantage on the field. “He was always a big kid — probably six feet tall and 200 lbs. in 8th grade,” Irwin said.

“He was always eating everything and anything, especially my spaghetti,” she said.

As a teenager, “he tested the waters and pushed the limits like any teenager but when it came down to it, he was a good kid,” Irwin recalled. “I never had to worry about him breaking curfew or anything. Sometimes, I had to push him out of the house — he loved being at home, loved being with me. His friends would usually come to my house.”

But as with any teenager, there were some difficult times, especially when his parents split.

“It was really tough for him being a teenager when his father and I separated but he pushed through it,” she said, adding that his motivation for school dipped during that time. “I told him, ‘I can tell you what to do but I can’t make you do it — it’s up to you if you want to make something of yourself’ and he decided that he did.’”

In 2010, Robinson and other members of the La Follette football team met President Barack Obama during an unplanned trip to the school.

“He was amazed that happened. I think that had a lot to do with him wanting to improve his academics,” said his mother, adding some time after that “he completely turned it around by himself and he ended up graduating six months early” from Sun Prairie High School last winter.

While in high school, Robinson worked at a restaurant and in a grocery store’s meat department. That’s also when he picked up longboarding, a hobby that quickly became an obsession, doing it day and night, weather permitting.

Irwin now keeps his longboard in a closet just off the kitchen. The wheels are worn and axles are loose from heavy use. It has the word ‘Golden’ scratched into the bottom, but “I never got a chance to ask him what that meant,” she said.

Tight with Family

Always close with his siblings, Robinson had plans to help his younger brother earn a football scholarship. “Terrell always saw a lot of potential in his younger siblings. He had big dreams for them,” said Irwin.

He was also known a mediator, often encouraging family members to settle their differences. “He was the glue that kept us all together. He hated when anyone argued, he couldn’t stand it,” she remembered.

He was close with his dad, whose family called him ‘Floppy’ because of a bent ear — a nickname he hated but seemed to tolerate.

He also wore a fisherman’s hat that seemed to invite a bit of ridicule. “It was Hawaiian-themed, pink and blue,” said Irwin. “He loved it but would get picked on for it — maybe that’s why he loved it so much.”

Court records show Robinson was diagnosed as hyperactive, but his mom downplayed that. “He was always rambunctious and energetic, it was just who he was,” she said. “His mind was going all the time with ideas. He bounced off the walls with ideas and plans from the minute he woke up to the minute he went to sleep every day of his life. They want to call that ADHD — I just think he was full of life.”

Some of those ideas included owning a business and he planned to enroll in business management at Madison College soon. “He wanted to own his own company and to tell everyone else what to do — he was good at that,” his mom joked.

And of his recent legal trouble with the armed robbery case, Irwin said it was his nature as a people pleaser that led him down that path and that he was coerced into taking part.

“He was somewhat of a follower — he just wanted to be liked,” she said. “He got himself into the trouble by going along with it. He would have never had done it on his own.”

But still, he accepted his role in the crime, Irwin said. “No one punished him for that more than he punished himself. He was very angry with himself for it,” she said, adding that he successfully completed more than six months of house arrest before he died. “He had to spend all last summer watching from the window, seeing everyone out on the block playing but he did it because he knew he messed up.”

After house arrest, he lived in the house on Williamson Street where he was killed, said Irwin. A couple days before that fateful night, he made his final visit to his mother’s home.

“They say that people do things before they die, almost like they know it’s coming. Well, he came here late that night saying he wanted to pick up some clothes but he didn’t even take any clothes. The kids were in bed because they had school and he went upstairs, woke them all up and got them out of their bed and hugged them all,” she said. “Then he came down and gave me a big bear hug and then went back upstairs before he left — even though I told him not to — and gave them all another hug and told them he loved them. And he hugged me again, gave me a kiss and told me he loved me. That was the last time I saw him.”